Spy Dust - Part 2: The 1985 Shadow War Between KGB and CIA in Moscow

More on My Arrest on Espionage Charges by KGB in Moscow from the Russian Documentary 'Spy Dust'

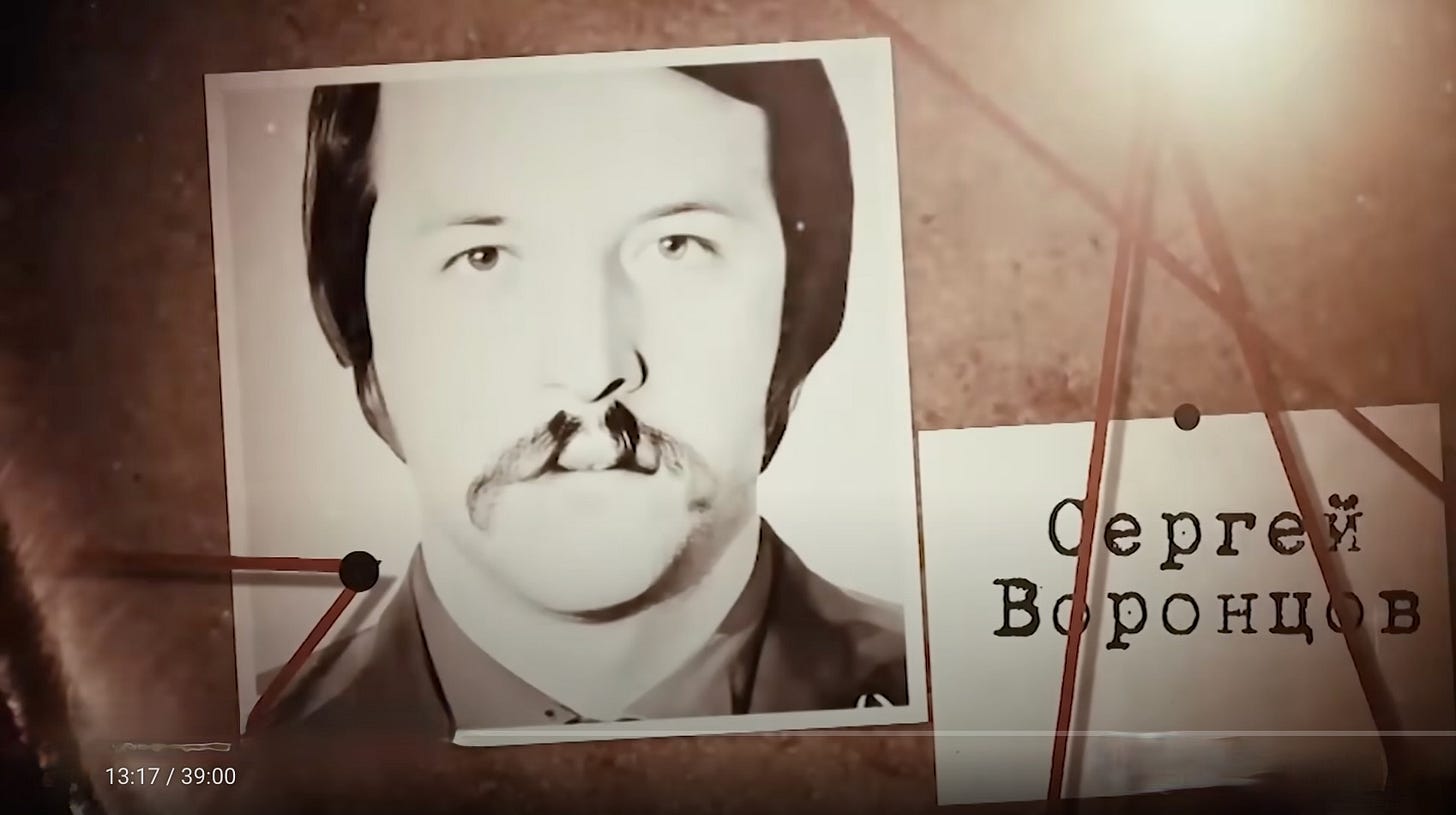

This one is for those who find ‘Cold War spy vs spy’ true stories interesting in their own right, even if not directly addressing the urgent present day matters that have been our main focus here at Deeper Look. In that vein, I previously shared Spy Dust Part 1 a 2023 Russian documentary that tells the story of a 1985 spy scandal in Moscow in which a KGB officer (Sergey Vorontsov) gave a CIA officer (me) a sample of a chemical tracking powder ( “spy dust”) that would trigger an international scandal similar to the “Havana Syndrome” issue we see today. Here is Part 2 of the same 2023 Russian Documentary, repurposed here as a magazine style article in English. This is all taken directly from the transcript of the Russian Documentary, written by Alexander Elbayev and directed by Julia Satarova, so the writing credits go to them — I’m just sharing what they wrote, with the proviso that it’s all basically accurate — and I know that for sure because I was at the center, alongside the KGB Agent Sergey Vorontsov, of the story they are tellng.

The “Artistic” CIA Officer

Only the most elite CIA officers were selected for service in Moscow. In 1985, one of their number was Michael Sellers, a promising young CIA operative. In 1984, Sellers arrived in Moscow, officially under the guise of the second secretary at the US Embassy. Born in 1954, Sellers was first recruited into the CIA while studying film at New York University. He trained at the agency’s secretive Virginia facility, known as “The Farm.” Over the course of his ten-year career, he conducted covert operations in Eastern Europe, Africa, and the Philippines, and he spoke fluent Russian—an invaluable skill in his line of work.

But Sellers’ cover was far from impenetrable. The KGB quickly identified him as a CIA officer and began closely tracking his movements. Over time, they developed a clear picture of his methods and his role within the agency. “We knew he was with the Central Intelligence Agency, and we followed his professional progress closely,” one former KGB officer recalls.

In the eyes of the KGB, Sellers stood out among CIA operatives for his creativity and flair. “He was the most artistic of all the CIA agents,” said Rem Krasilnikov, a legendary Soviet counterintelligence figure who headed the ‘Second Chief Directorate’s American Department throughout the 1980s. Sellers, it seemed, had a flair for performance, blending his espionage work with a love for the arts. He frequented Moscow’s theaters and concerts, played guitar, and even released a record album in the United States. Krasilnikov believed Sellers’ artistry was more than just a hobby—it was an integral part of his tradecraft. Sellers had a reputation for being a master of disguise and transformation, using it to escape detection by the KGB when going operational.

“He was quite the actor,” says Sobol. “There were many examples of his use of disguise. Sometimes he used inflatable mannequins. Other times he would make himself up to look like another American diplomat—matching clothes, wigs, the whole package. The Americans used this disguise technique a lot. Sellers learned it well as a cadet at the CIA school and put it to good use.”

According to KGB assessment, Sellers’ charismatic personality was another tool in his espionage kit. He was a sociable and easygoing diplomat, capable of slipping into any social situation and winning people’s trust effortlessly. His own description of his work as a CIA operative was less about espionage and more about theater. “I actually thought of what I did in Moscow as a kind of theatrical performance,” Sellers later reflected. “Because I was always under surveillance. And when you’re under surveillance, you’re performing a role for them. You’re trying to convey the story you want to tell. My story was that I was very happy to be in Moscow, and that I loved and respected Russian culture.”

By the time Sellers had been in Moscow for several months, the KGB had built up a detailed profile of his movements and activities. But as Sellers was perfecting his performance, something unexpected occurred. In late 1984, the CIA received a tantalizing offer: a Soviet counterintelligence officer was ready to provide his services as an informant. That officer’s name was Sergei Vorontsov, and his decision to turn against the KGB would set the stage for one of the Cold War’s most gripping intelligence dramas.

The Betrayal of Sergei Vorontsov

The question of why someone betrays their country is as old as espionage itself. And, according to those who worked in Soviet intelligence, the motivations are often depressingly simple. “Why did Vorontsov volunteer? Why do traitors appear in intelligence services, including ours?” muses retired KGB officer Valentin Sobolev. “I am absolutely convinced that the overwhelming motive for people who are on the pulse of betrayal is profit. Secondly, this is also pride. When a person feels that he is undervalued, that he deserves something more.”

Sergei Vorontsov’s story of betrayal began in November 1984, not in the cloistered offices of the CIA but in a modest service apartment in the Chertanov district of Moscow. At the time, Vorontsov, a major in the KGB, lived there with his family. By all accounts, he had a bright future ahead of him. At just 37, he had climbed from the position of a simple operative to deputy head of his department—a significant achievement in an organization where advancement was hard-won. But as quickly as his career had risen, it collapsed.

“We had special apartments, safe houses, where we would work,” explains retired KGB officer Sergei Terekhov. “Allegedly, Vorontsov and others in his department organized drinks and parties there. Someone reported this to management.” The official story was that the drinking led to a breach in discipline, but many suspected it was a pretext for something else. Following the report, Vorontsov was demoted to the rank of senior operator.

The demotion hit him hard. According to Terekhov, Vorontsov believed the incident was only a superficial excuse. He was known to be outspoken, clashing frequently with his superiors and pushing for more promotions. His combative nature had likely earned him enemies. “He thought his sharpness and bluntness caused him trouble,” says Terekhov. “It was probably resentment over this that got him into trouble with KGB management.”

Historian Andrey Bednev sheds further light on the situation. “Vorontsov’s career was excellent, but suddenly it went astray because of a conflict with his leadership,” Bednev explains. “He removed an inconvenient deputy, but this move backfired. His personnel file was marked with a note that he would not advance any further.” That note in his file was, in effect, a career death sentence within the KGB.

The demotion left Vorontsov angry and disillusioned. It also left him in financial trouble. “He was looking to solve the financial problem at the same time,” Terekhov adds. The combination of career stagnation and monetary strain made him a prime candidate for defection. And, as Terekhov observes, “He believed betraying the KGB would also be a way to take revenge on his boss.”

But it wasn’t just about revenge or even just money. Vorontsov had an expensive hobby. Unlike most Soviet citizens, who sought out consumer goods from the socialist camp, Vorontsov had a passion for pre-revolutionary furniture—luxury items that were hard to come by in the Soviet Union. His desire for these high-end antiques only exacerbated his financial difficulties, pushing him further toward betraying his country.

It was around this time that Vorontsov first made contact with the CIA, and he chose an unusual path to do so. John Feeney, an American diplomat who worked at the US Embassy in Moscow, was one of the people Vorontsov noticed. “Feeney was considered a pure diplomat,” recalls a retired KGB officer. “He never went to restaurants, and he was not known to have any connections with American intelligence.” This low profile made him an attractive target for Vorontsov, who was searching for a safe way to reach the Americans.

Meanwhile, the CIA was using its own unconventional tactics. In the 1970s and 80s, the pedestrian areas around the US Embassy in Moscow were swarming with KGB operatives, making it difficult for CIA officers to avoid surveillance. “This area had no concrete slabs—there were reinforced concrete slabs later—but at the time, the area was packed with cars,” notes retired KGB officer Pesok. What the KGB didn’t know was that embassy cars themselves were being used by the CIA in its intelligence activities. “Few people know this,” Pesok continues, “but the Americans left the rear windows of their cars slightly open, creating gaps that were crucial for passing information.”

This hidden world of surveillance, betrayal, and clandestine communication set the stage for Vorontsov’s eventual collaboration with the CIA. His resentment, financial woes, and passion for luxury would push him to cross the line, and in doing so, he would become one of the most damaging moles the Soviet Union had ever faced.

The Soviet Furniture Craze—and a Diplomat’s Secret Role

In the 1980s, Soviet citizens were grappling with a deep frustration familiar to many in socialist economies—furniture shortages. The drab furnishings available to most Soviet families couldn’t compete with the allure of East German wall units, Yugoslav sofas, and Romanian bedroom sets. These items, seen as the height of luxury, were the dream of millions of Soviet households. Yet acquiring them often meant waiting months, if not years, for the availability to purchase.

However, as Soviet citizens waited in line, the American diplomats in Moscow had a very different approach to decorating their homes. American diplomats also had to purchase furniture, but not the kind Soviet citizens sought. They preferred antiques, which were definitely not the norm in a socialist country. Fortunately for the diplomats, there was a particular store where they could buy vintage items, and the US Embassy staff frequented this shop with great enthusiasm, searching for unique pieces to bring a bit of home into their residences.

One of those American diplomats with a love for antiques was John Feeney, the second secretary of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. Feeney often visited a small shop on Pyatnitskaya Street in the center of Moscow, and his habit of shopping there did not go unnoticed by the KGB. “When I went to meet Sergei, I knew that he visited this antique store,” recalls retired KGB officer Vladimir Nechaev. “He would go in, stay for a while, and leave the car parked.”

Feeney was considered a “pure” diplomat by the KGB, and his unassuming status made him a perfect candidate for someone seeking to make contact with the Americans discreetly. Sergei Vorontsov, facing career stagnation and personal frustrations, saw an opportunity in Feeney’s regular visits to the antique store. After observing him several times, Vorontsov concluded that Feeney moved through Moscow without being followed by KGB surveillance teams—a rare occurrence for an American in the city.

“Vorontsov studied the situation and saw that Feeney was suitable,” Nechaev explains. “He saw him come and go several times, without any sign of surveillance. It was good.”

Vorontsov, sensing his chance, prepared a letter for Feeney. But this was no ordinary note. Enclosed was a copy of the Top Secret Bulletin of the Second Chief Directorate, a critical document outlining the techniques used by Soviet counterintelligence against the CIA in Moscow. For the Americans, this was a highly valuable gift—a goldmine of information that could give them a significant edge in the ongoing Cold War espionage battle.

The letter was Vorontsov’s opening gambit. He was ready to betray the very organization that had once been the cornerstone of his life. To establish further contact with this new Soviet defector, the CIA tapped one of its most promising young officers: Michael Sellers. Sellers, with his experience in Moscow and his reputation for ingenuity, was the perfect candidate to manage the high-stakes relationship with Vorontsov, a man whose betrayal could reshape the intelligence landscape in Moscow.

Meeting the Mole: The CIA and “Agent Cowl”

Michael Sellers had been tasked with making contact with a new potential Soviet informant. The man was known only by the pseudonym “Stas,” a mystery figure who had approached the Americans with sensitive information. “When I went to the first meeting, we didn’t know his real name,” Sellers recalls. “We only knew him as Stas. I was in a light disguise, and there was nothing on me that could identify me.”

Sellers’ mission was clear: determine the identity and reliability of this new source. Armed with a concealed voice recorder, Sellers spent hours walking the streets of Moscow alongside “Stas,” probing for details about his life—his work, his family, and his political views. But the man who would later be identified as Sergei Vorontsov proved to be cautious, deflecting any potentially incriminating questions. From the outset, he made it clear that he had no intention of defecting to the West. His only interest, it seemed, was financial.

The initial meeting gave the CIA enough to work with. Vorontsov’s professionalism stood out, and after analyzing the voice recording, the agency concluded that this was no amateur. This was a man who knew his trade. “He was a very interesting character,” Sellers reflects. “Slightly aggressive, a cautious person.” And with that, the mole known as Agent Cowl was officially added to the CIA’s files.

It wasn’t just the man’s demeanor that left an impression. At that first meeting, Vorontsov was paid 15,000 rubles—a staggering sum at the time. As host Vladimir Litvinov explains, “For comparison, a Zhiguli car cost about 7,000 rubles, and people saved for years to buy one. With 15,000 rubles, you could purchase a brand new Volga.” But Vorontsov had no interest in cars. Instead, he used his first payment to buy his wife a mink coat, an extravagant purchase that was as rare as it was risky.

In the mid-1980s Soviet Union, a high-quality fur coat made from natural mink was a luxury item reserved for the privileged few. Such coats could only be bought in special stores intended for party officials, or through the Berezka Network, a chain of stores where Soviet citizens returning from overseas trips could spend foreign currency. For most people, acquiring such a coat meant turning to the black market, where prices were exorbitant.

There was little chance that Vorontsov’s wife knew how much her new mink coat had cost, or where the money had come from. “Of course not,” says retired KGB officer Sergei Terekhov. “There are only a few who involve their wives and loved ones in espionage matters.” Vorontsov’s decision to buy such an extravagant gift wasn’t just a financial risk—it was a personal one. “It was his decision. This is his destiny,” notes Vladimir Nechaev, another retired KGB officer.

Despite the risk, Vorontsov’s devotion to his family was clear. “For the sake of his family, he was ready to attract attention to himself,” Nechaev continues. “He loved his wife very much and doted on his daughter.” Terekhov adds, “The family was small but very friendly. His daughter really liked him. If you ignored the fact that he was a mole and a traitor, you would never know from his family that he was betraying the Motherland.”

The KGB Closes In

But while Vorontsov was playing a high-stakes game of betrayal, the KGB was closing in on him. The team tasked with finding Agent Cowl was working with only the most basic information. “The mole introduced himself to the Americans as Stas,” explains the documentary’s host. “Hardly a real name. Most likely a pseudonym.” There was another small but critical clue: the mole had once traveled to Ireland. This piece of information came from Aldrich Ames, the infamous CIA officer who had been spying for the Soviets, who learned it by studying the tape recording of Sellers’ first meeting with Vorontsov.

Even with this tidbit, the investigation remained complicated. The need for absolute secrecy made the KGB’s job harder. “It was secret that we were working to find an American intelligence agent in the KGB’s own ranks,” Terekhov explains. “I knew no more than 10 people in the KGB who knew about it. Even fewer, actually. It was difficult to work among colleagues, all of whom were counterintelligence agents. No one—not a secretary, not a typist, not even someone in the records bureau—could know who we were hunting or why.”

The investigation was painstakingly slow. Even something as simple as requesting the personal files of KGB officers who had traveled abroad could arouse suspicion and potentially tip off the mole. To avoid this, the operatives had to go through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, manually combing through the records of every Soviet citizen who had visited Ireland over the years. “It took about four months,” Terekhov recalls. “We had to go through huge books, huge magazines. When we finally wrote out the list, it was about a meter long, maybe more. By then, we were starting to doubt whether we would ever find this person.”

To be continued . . . . .

Also: DEEPER LOOK is 100% reader supported. i appreciate your support to the work I’m dong here. Please consider a free or paid subscription. Both help and are appreciated.

How does a CIA Russia specialist in Moscow acquire nerves of steel?

When did you learn of Ames' betrayal?

As you stated in your article,

“I am absolutely convinced that the overwhelming motive for people who are on the pulse of betrayal is profit."

I think we're witnessing this on a grand scale in the Trump Administration right now!!!